Boat Rocker Media had a hit on its hands. The Next Step, a tween-targeted show about an elite dance troupe, drew the highest ratings the Family Channel had ever seen for a premiere at the time, with 574,500 people tuning in. Over five seasons, the Canadian-made series found an audience – in more than 120 countries, viewers were following the drama of a telegenic squad of teen dancers as they competed to win championships, formed friendships and rivalries, and pursued their dreams. The company drew in viewers to its YouTube channel as well, where it posted dance sequences regularly watched by tens of thousands online.

“It built a global juggernaut,” said Jon Rutherford, president of rights at Toronto-based Boat Rocker.

But by the sixth season, Boat Rocker’s financing in Canada was no longer enough to get production off the ground. DHX Media Ltd., which now owned the Family Channel, was still paying a fee to license the show, but “their total financial contribution was much lower,” Mr. Rutherford said. So last summer, Boat Rocker turned to U.S. channel Universal Kids, seeing an opportunity to work out the first deal for the show with a major American TV broadcaster. In August, Boat Rocker announced that Universal Kids had acquired the rights to the first five seasons and would be a production partner on the sixth.

It might seem surprising that a hit show would face an investment shortfall in Canada. But it didn’t come as a surprise to Boat Rocker, because they had already noticed the landscape in kids’ TV production start to shift drastically. “In the golden era,” Mr. Rutherford said, “you could get upwards of 80 per cent of your financing in Canada” to get a show off the ground, when taking into account the broadcasters’ investments as well as government-led incentives for Canadian content. (A “semi-scripted” show such as The Next Step – scripted, with improvisational scenes – typically has a budget of roughly $375,000 to $500,000 a season.)

In this new era, Canadian financing often falls short. The Next Step required financing from both the U.S. and Canadian broadcasters, other international partners and funds Boat Rocker itself put up for the show to go on. It was hardly an isolated case.

Stories such as these are echoing across the Canadian TV production landscape. As viewing habits shift – particularly among the youngest audiences – and competition from streaming services such as Netflix has increased, the television broadcasters that have traditionally funded Canadian content production are spending less on funding kids’ shows. Recent regulatory changes that give broadcasters more freedom to choose where they want to spend money have contributed to the shift. So have restrictions on advertising that make kids’ shows less lucrative for broadcasters.

The result is massive industry upheaval that has upended the traditional funding model for shows and led to an alarming decline in production: Children’s and youth production fell by about 17 per cent in the fiscal year from April 1, 2016, to March 31, 2017, according to the Canadian Media Producers Association (CMPA).

Joy Rosen, chief executive and co-founder of Portfolio Entertainment, says she began noticing a shift in the industry about two years ago. “It’s been very slow,” she said. “The number of shows getting picked up is limited.”

Portfolio has adapted, Ms. Rosen said, by depending more on global players to commission its content. It also made a move some years ago to ensure the business was not solely dependent on production, but is also involved in distribution. And it has seen a major pickup in so-called service work, an industry term for work on shows that aren’t technically based in Canada. “The companies that will suffer the most are the ones that don’t have those global relationships,” she said. “And the ones doing the best are those that are funding shows elsewhere and viewing Canadian funding as supplementary.”

Under the industry’s longstanding financing system, Canadian broadcasters were the first stop for production companies seeking funding – both because they would invest in commissioning those shows, but also because each broadcaster oversees an “envelope” of funding from the $350-million annual Canada Media Fund, a partnership funded by the federal government and Canada’s cable and satellite distributors. Broadcasters can choose to contribute CMF money to any show where they contribute a certain level of funding (in the case of English-language children’s and youth shows, the contribution must be at least 25 per cent of overall production costs). Having a domestic broadcaster on board can also trigger tax credits.

The system helped build a global reputation for Canada as a powerhouse in kids’ content – thanks to factors such as the National Film Board’s early investment in animation, starting in the 1940s; the CBC’s support for groundbreaking programs starring Ernie Coombs (a.k.a. Mr. Dressup) and Fred Rogers (a precursor to Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood called Misterogers); and what some say is a particular Canadian sensibility that sells well in kids’ entertainment (think Paw Patrol and the many Degrassi spinoffs).

Now, some in the industry are raising the alarm that this system is disappearing. The federal government is responding by reconsidering its approach to the industry, with a review of the Broadcasting Act. In a report in May, the country’s broadcast regulator acknowledged the current model for regulating the industry is “unsustainable.”

But some – including Lisa Olfman, Portfolio’s other founder – believe the changes may come too late. “I think many companies will not make it,” she said.

The pressures that kids’ producers face now are partly because of regulatory changes that were intended to keep pace with a TV industry in flux. In 2010, the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission introduced a new licensing policy that allows broadcasters to spread Canadian content spending across the networks they own. Before, spending levels were dictated channel by channel.

The CRTC wrote at the time that the change would “benefit the broadcasting system as a whole” by giving broadcasters “greater flexibility” to direct spending to the TV channels that were most effective in drawing audiences and revenue. But broadcasters still had to fill about half of each channel’s schedule with Canadian content (including mandated exhibition in prime time). Then, in 2016, quotas changed to 35 per cent. Kids’ producers say that’s when they began to take a hit.

One reason was ad revenue. Regulations on advertising to kids limit how lucrative children’s TV can be. Canada’s Broadcast Code for Advertising to Children restricts the types of ads that can appear during kids’ programming, as well as how much a network can sell: No more than a total of eight minutes of advertising is allowed per hour and the same commercial cannot run more than once in a half-hour period. (In Quebec, commercial advertising directed at children under 13 is prohibited.)

For most broadcasters, it’s simpler – and more lucrative – to sell ads during programming targeted at adults. And under the new CRTC policies, they had more freedom to invest in that programming.

“If you talk to a broadcaster, they’ll say, great, that’s what we needed,” said Mark Bishop, co-CEO and founder of marblemedia Inc., which creates shows it has sold in more than 150 countries. “If you talk to anybody else in the industry, they’ll say that was the kiss of death.”

The two biggest children’s broadcasters in Canada, Corus and DHX, have faced challenges that have forced them to assess how they invest in content. Corus has taken a “pause” on commissioning as much kids’ content as it used to, said Lisa Godfrey, vice-president of original content for the company that owns YTV, Teletoon and Treehouse among its portfolio of specialty channels. Corus is looking to “optimize” content investments to focus on channels “that we can monetize the most,” Ms. Godfrey said.

Last October, Family Channel owner DHX launched a “strategic review” to fix what ails the company. Following a $345-million (U.S.) investment in 2017 for the rights to the Peanuts franchise and Strawberry Shortcake, DHX’s financial results slipped, triggering questions about its management. The stock lost half its value in a year. Less than a year after buying the Peanuts stake, DHX sold half of it to Sony Corp. The strategic review is ongoing. Production companies say DHX, which has financed shows in the past such as The Next Step and animated series Fangbone!, isn’t commissioning as much as it once did, though a company representative denies this, saying it has commissioned 16 projects from 10 independent producers over the last three years. “I can’t speak for the whole industry, or to why individual producers might say we aren’t commissioning,” spokesperson Shaun Smith said in an email. The company declined requests for an interview.

Public broadcasters such as CBC and TV Ontario (TVO) continue to invest in kids’ shows, but their budgets can’t make up for the shortcomings that now exist as private broadcasters change their priorities.

Vince Commisso, co-founder, president and CEO of 9 Story Media Group, says his company hasn’t had a commission for a show from a Canadian broadcaster since 2015.

The traditional funding model was never perfect, he says. “It was perhaps unwieldy and perhaps placed too great a burden on the broadcast entities. But the way to deal with it is not to have it come to a screeching halt.”

Regulatory changes are just one part of the story: Streaming platforms are also changing the ways that kids consume entertainment.

Gone are the days when broadcasters only competed against one another. Now, they’re vying for kids’ attention with streaming services such as Netflix, Amazon Prime and YouTube.

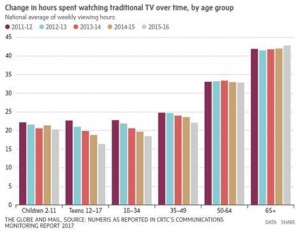

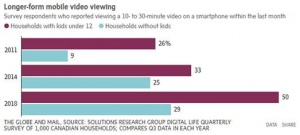

From 2011 to 2016, the hours spent viewing traditional TV each week declined most sharply among teens of ages 12 to 17, according to the CRTC, while declines among kids under 11 were more gradual. At the same time, kids have led the way in the growth of digital viewing: In its surveys of Canadians’ digital media habits, Toronto-based consultancy Solutions Research Group has found that households with children under 12 consistently report more video viewing on digital devices than households without kids. And while for some time they lagged in cutting the cord, the same research found that this year, 21 per cent of households with kids reported having no TV subscription compared with 15 per cent of adult-only households.

At the Kidscreen conference in Miami earlier this year, producers noticed that Netflix sent a much larger team of people than it had in previous years. Apple recently hired Tara Sorensen, former head of Amazon Kids, signalling that children’s content is a priority for the tech giant. In June, reports emerged of a deal that will see Sesame Workshop, the non-profit organization behind Sesame Street, produce kids’ content for Apple. And children’s entertainment juggernaut Disney has announced plans to launch its own streaming service.

In one sense, the rise of such services is good for kids’ TV producers because there are more buyers looking for content. But producers trying to sell to the likes of Amazon and Netflix also face more intense competition – from producers all over the world – than they contended with in the past, when their first sale was to Canadian broadcasters. Deep-pocketed streaming services have also raised the bar on production values, many in the industry say, making it harder for budget-strapped Canadian production companies to compete.

And kids’ TV habits are changing fast.

“We are now programming and producing for a generation of kids that were born with Netflix in existence,” said Jennifer Dodge, executive vice-president of Spin Master Entertainment, a division of the toy company Spin Master Corp. “They were born having tablets. They pick and choose things they’re interested in, and fall down that YouTube rabbit hole where there are a million videos suggested based on what you’ve watched and what you like.”

Spin Master’s hit show, Paw Patrol (the top U.S. TV preschool show with two- to five-year-olds for two years running, and watched in 160 countries), benefits from the viewership it attracts by being available on Netflix in Canada. But Ms. Dodge noted the flexibility in its broadcast deal with TVO – which allowed episodes to go to a streaming service after a certain window of time passed – is becoming much rarer these days.

That’s because broadcasters are trying to persuade viewers to stick with the TV system. So they are negotiating to own more show rights, in order to keep content for their own TV channels, video-on-demand and associated streaming offerings (many of which are limited to TV subscribers).

It also means broadcasters that own production studios – as both DHX and Corus do – have more incentive to make more shows in-house and keep more of the revenue.

Corus’s Ms. Godfrey points to Mysticons, a show produced by Corus-owned animation house Nelvana, as an example. The show about four girls who are transformed into mystical warriors airs on Corus’s Canadian channels, YTV and Teletoon, and because Corus owns the show, it also makes money from a U.S. broadcast deal with Nickelodeon. Corus also benefits from merchandising sales and from brand partnerships such as a recent deal with Burger King that offered Mysticons figurines with kids’ meals in 7,400 restaurants in the United States and Canada. This is ideal for Corus: Owning intellectual property means finding more revenue opportunities. If a show can become a book, a movie, a toy line and a basis for a branding deal, Corus wants to reap all the benefits. Before, a broadcaster might have made plenty of money on a show through TV advertising; nowadays, they need to find revenue elsewhere, too.

“That is the change in the industry: the domestic airing of content is not enough to pay for these shows, to monetize these shows and to have a successful overall broadcasting business,” Ms. Godfrey said.

The new realities of the Canadian market are forcing some kids’ production companies to seek funding elsewhere. Anthony Leo, co-president of Aircraft Pictures and a recent Oscar nominee as producer of the animated film The Breadwinner, says he no longer thinks of Canadian broadcasters as the “first port of call for a show.”

“We’re relying less on them and going internationally to get that first piece of financing,” he said. It’s been a couple of years since he’s been able to fund a show under the old model. “It’s really changed how we get a show made.”

That worries some industry representatives.

“Domestic demand by Canadian broadcasters has been one of the pillars of the Canadian kids industry. It has helped serve as a launching pad not only for national success, but global success,” said Reynolds Mastin, president and CEO of the Canadian Media Producers Association.

“Kids’ content in Canada has been some of the most successful that the country has produced around the world. It has sales in hundreds of territories,” said Valerie Creighton, president and CEO of the Canada Media Fund. “… We have to be really mindful that we don’t lose that traction. We don’t want to regress in terms of the creativity of our companies and their success. That’s the part that keeps me up at night.”

When the main financing partner is not a Canadian broadcaster, there is less pressure to keep the show Canadian; a production partner might want to use a writer they know in L.A. or a director they’ve worked with before. It can also whittle away at Canadian elements in the story.

“If we’re not careful, we very quickly could become just a service arm for the U.S. We’ll have a talent drain of people leaving – we’re already seeing it now,” marbelmedia’s Mr. Bishop said. “And I worry we’re going to lose the ability to tell Canadian stories to Canadian kids.”

All of this has raised questions about whether the system for funding kids’ production in Canada needs a rethink. Last March, the federal Canadian Film or Video Production Tax Credit was opened up to include shows that play on broadcasters’ websites and on streaming services such as Amazon Prime and Netflix. While it was a welcome move, that tax credit only accounts for 10 per cent of kids’ content financing, according to the CMPA. A much larger portion of the funding for kids’ shows – including provincial tax credits and the CMF – is still tied to deals with a Canadian broadcaster or a streaming service owned by one.

At Aircraft, Mr. Leo said he is finalizing deals for a show based on a well-known Canadian young adult book series. But because the majority of its funding comes from non-Canadian sources, he does not have access to CMF resources. “The answer is not for broadcasters to pony up more,” he said, but added that producers making Canadian content should be able to access funding that was set up to support it.

“Canadian producers having less financial resources from Canada to bring to the table when packaging a show for an international audience doesn’t necessarily mean that fewer shows will be made in Canada – Canadian producers have a great reputation for producing high-quality kids content,” he said. “The danger is that fewer Cancon shows are made and that more Canadian stories will be owned by foreign buyers instead of Canadian producers.”

The CMF is going to be reviewing its financing models this fall. Under its existing terms of agreement with the federal government, it only triggers financing once a broadcast agreement is secured with a Canadian broadcaster.

“Because of digital disruption, the fact that audiences are migrating … that [financing] structure is crumbling a bit,” said Ms. Creighton of the CMF.

The CMPA has formed a kids committee to address the challenges the sector is facing and is examining whether different triggers are needed to make CMF money available more widely.

The challenge is that non-Canadian streaming services do not have to pay into the system through vehicles such as the CMF – Canadian broadcasters and cable and satellite companies do and they argue that companies that don’t contribute should not be able to top up financing of their shows from that pot.

In a report released in May, the CRTC argued that digital players including streaming services, wireless companies and internet service providers should all be required to contribute to funding for Canadian content. The CRTC report was commissioned by former Heritage Minister Mélanie Joly and is intended to inform the review of the Broadcasting Act and the Telecommunications Act that Ms. Joly initiated along with Innovation Minister Navdeep Bains.

Canada is not the only jurisdiction struggling with this: Britain recently announced a new £60-million ($100-million) fund dedicated to supporting children’s television.

In a perfect world, Mr. Leo said, he’d like to see streaming services such as Netflix and Amazon pay into the system the way broadcasters do and, therefore, be able to access CMF funding for qualifying productions that air on their platforms just as Canadian broadcasters do. But he worries, too, the challenges in kids’ TV are just a sign of more to come.

“Their audiences are right in that generation that has grown up with YouTube and not Saturday morning cartoons,” he said. “I wonder sometimes if the kids’ broadcasters aren’t the canary in the coal mine.”

FUNDING IN FLUX

To trigger funding from the Canada Media Fund, a show needs to have a certain amount of financing from a Canadian broadcaster – and the numbers tell a story.

In the 2015-16 fiscal year, 19 per cent of the CMF’s financing for English-language TV and complementary digital production (including websites, apps and games) went to kids’ programming; that dropped to 12 per cent in 2016-17 and stayed at that level in 2017-18. (As with the rest of the media business, the French-language market is much healthier when it comes to homegrown content.)

“There certainly have been declines in CMF-financed kids’ content,” CMF president and chief executive Valerie Creighton said. “It’s a concern to us.”

Independent production funds such as the Shaw Rocket Fund have also noticed a difference. (Shaw Communications Inc. contributes to the non-profit fund, but it is independent from the company.)

“We did see a drop in the amount of producers that are getting commissions for programming and applying to us for investment,” Shaw Rocket Fund CEO Agnes Augustin said. “Also, we’re seeing a need for higher investment for producers, because there isn’t as much money being triggered elsewhere.”